With the advances in medicine and technology, patient longevity has dramatically increased. Patients now live longer to have multiple, complex medical problems. In the past, primary care physicians were taking care of their own patients in outpatient settings as well as in hospital settings. With the declining reimbursement, increasing overhead and the pressure to be more efficient, primary care focuses more on outpatient care, whereas care of patients who suffer from complex medical issues in hospitals are deferred to physicians who choose to practice only inpatient hospital medicine, also known as the hospitalist.

Hospitals are very complex organizations with several different sets of providers which try to work as a team to deliver effective care to patients. This team is comprised of referring physicians, hospitalists—who practice medicine mainly in the hospitals—intensivists—who provide care to critically ill patient in the intensive care unit—specialists—like cardiologist or neurologist—surgeons, nurses, therapists, and an array of technicians and technical support teams.

To keep pace with the changes in the healthcare system and declining reimbursements, this model was very well received by the hospitals and the managed care companies. Hospitalists were able to provide efficient, cost-effective care for patients who were admitted to the hospitals. This helped the hospitals reduce the length of stay and cut costs. Patients, on the other hand, were able to get care by physicians who specialized in taking care of sick patients who were admitted to the hospital in a timelier manner. This created a win-win situation for patients, hospitals and primary care physicians.

But wait a second.

If this is true, why is there still an increase in healthcare costs? Why is there a high level of dissatisfaction among providers as well as patients?

“What if a patient comes to the emergency room and complains of mild chest pain, but the initial laboratory test is normal?”

At first glance, this system appeared good. From the patient’s point of view, it helped them get timely “treatment of [their] disease.” But, what about the second component that care must be personal? In the midst of trying to provide the best care for the treatment of disease, we forgot the patient and their preferences. Now, nearly every day, patients are seeing different hospitalist and specialists who are experts in their own area. Every one of them tries to be compassionate and address and treat patients’ conditions.

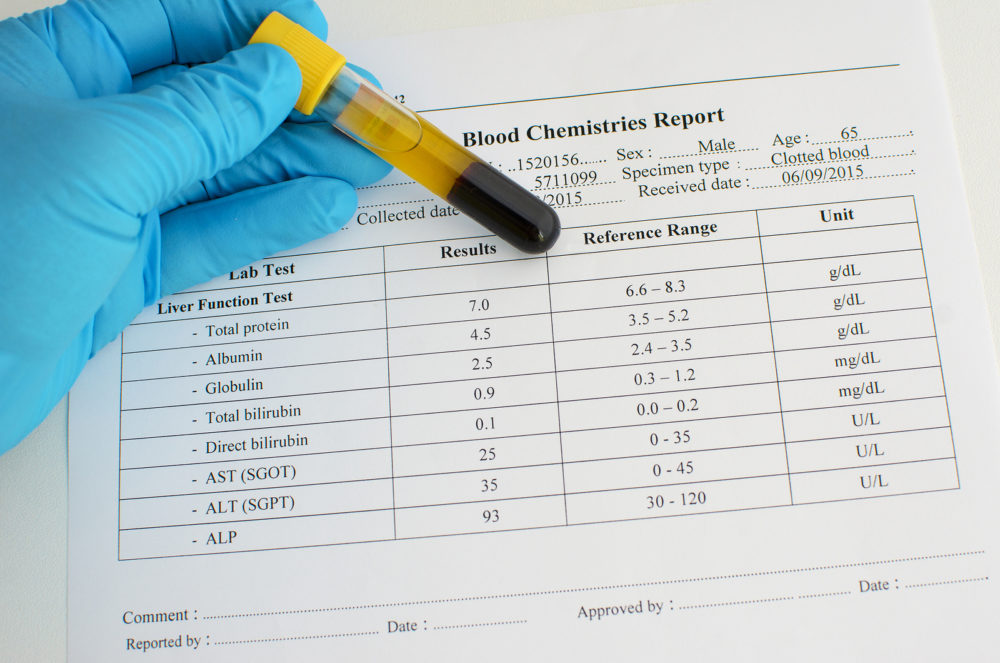

But do all of them really know the patient and their preferences? Do specialists know what they like and how they want to be treated? The focus went from personal care to disease-oriented care. Patients have become part of the big technological plant where they go through a barrage of investigation via blood tests, X-rays, CT scans, MRIs and other interventional diagnostic procedures. Many diagnostic and interventional tests are duplicated as they are completed at different points and no records are available.

In other cases, the patient is too ill to volunteer this historical information. This leads to more duplicate diagnostic tests, resulting in patient discomfort, procedure related risk and complications, and increases in the healthcare cost.

One day, my dad told me that he had some pressure sensation in the left arm all night long. I took him to his cardiologist, and the electrocardiogram was unchanged from a few months ago. His stress test was non-significant. I told the cardiologist that my dad has a very significant tolerance to pain and has never ever complained, even with his strong history of heart disease. He underwent a heart catheterization, and he was found to have significant blockage of his heart vessels and required five vessel bypasses.

Similarly, what if a patient comes to the emergency room and complains of mild chest pain, but the initial laboratory test is normal? It is common that the hospitalist feels that there is no reason to admit the patient. But that is where a primary care physician, who has known the patient for years, can say that the patient has a high tolerance of pain, and if they are complaining, then the matter must be examined further.

“Will the patients’ hopes ever be realized, or will that be buried under the volumes of scientific data forever?”

In this time and age, healthcare has become fragmented. With every physician focusing on the data points, no one has the complete picture. It is as if four blind people were asked to feel different parts of an elephant; each will describe it differently and come to a totally different conclusion. Healthcare has tried to get the picture and image clarity by the electronic medical record, but still, there is significant fragmentation in the electronic data sharing barriers. Different hospitals, primary care providers, laboratories, imaging centers, and specialists are using different electronic healthcare systems which make data sharing and interface challenging.

To address the provider-patient relationship, healthcare systems place a significant emphasis on patient satisfaction scores. Hospitals are trying to improve the patient satisfaction score by determining how quickly the call lights are answered, patient rooms having televisions with more channels, and warmer food with a better dining experience for patients and their family members. Additionally, there has been an increased importance in making visiting hours more accessible to family members.

Furthermore, more hospitals are implementing gift basket and night turn down service for VIP patients. The challenge is where the complex medically ill patients fall. Patients are not usually the ones who are filling out the surveys!

The nurses and physicians are all focused on the computer data entry and writing long notes in the chart to comply with the insurance companies’ requirements, but who is spending time with patients at their bedside, holding their hand and giving them their time?

These challenges have been compounded by newer generations of healthcare providers who are technologically savvy, have resorted to looking at the data points and are still trying to create the picture. The art and value of patients has been lost while trying to perfect the data points and science.

Patients are eagerly waiting to listen to the voice and see the face of their primary care providers, who they have trusted for years, rather than seeing several new physician faces on a daily basis. Will the patients’ hopes ever be realized, or will that be buried under the volumes of scientific data forever?

Recent Comments